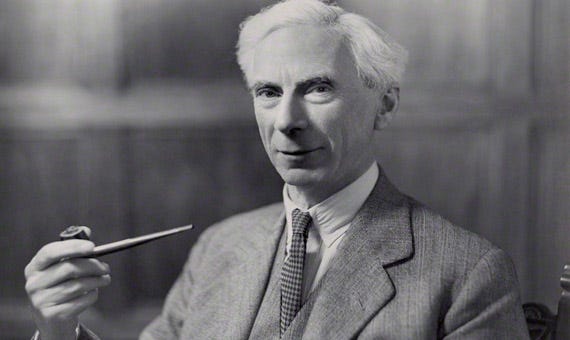

I took this classic 1925 essay by Bertrand Russell as a blueprint for a not-so-short manifesto and introduction to AutóMata. The order of some sections has been switched around a bit, and I made no effort to emulate any of Russell’s original points or arguments; I just used the section headlines as writing prompts. I do not intend to flesh out all the arguments in this piece, so some of it may come out as somewhat aphoristic or glib. I’ll do deep dives on the reasoning for my positions eventually—that’s what this space will be for.

Nature and Man

I should begin by specifying that I’m not only a physicist but a physicalist and, as far as I can remember, always have been. For now I will leave the arguments for physicalism for another time and skip directly to state its conclusion: there is no such thing as a non-physical entity, and indeed there can’t be, because the notion of a non-physical entity is gibberish. Sometimes this view is also known as naturalism or materialism. I find the choice of nomenclature to be a matter of what one wants to emphasize. Physicalism will be a common theme throughout this article (and the whole of AutóMata), and many of my views on different topics follow from it. I consider the supernatural to be not only inexistent, but also incoherent—hence it cannot exist. Also, I don’t think concepts or abstractions exist in the same way as fundamental particles, apart from the trivial sense that they reside in physical brains. I have always been an atheist as far as I can remember, though I did not associate it with materialism explicitly until adulthood.

As shortcuts of language, it is sometimes practical to use abstractions or stories to help us make sense of the world and our place in it. But these are only practical shorthands for the real stuff that exists and of which everything is made of: fundamental particles living in spacetime. This way of thinking about things is commonly known as physical reductionism. Many people speak of reductionism with derision, but I have found that even the ones worth taking seriously do so only with arguments from semantics or practicality, not soundness, and certainly not evidence. They mistake certain derivations or calculations from fundamental objects and their interactions being intractable or impractical with their being untrue. Whatever else may be considered to exist is only a convenient shorthand for the underlying fundamental physics.

One of these shorthands is ‘humanity’, itself a particular case of another larger category known as ‘life’. Under physicalism, there is no escape from the conclusion that life, and therefore humanity, is a collection of different kinds of self-replicating mechanisms—we are meat robots, as I’ve seen said in some places (the title of this publication is a play on this conclusion and my last name). This is in no way belittling—what matter can do is amazing! No myth, ancient or modern, could have imagined what we now know matter can do. Given enough time and a suitable source of constant energy, it can create flowers, whales, humans, cathedrals, pyramids and, most wondrous of all, knowledge about those things and many more. The way Carl Sagan once put it is that “we are of the Cosmos”, a way for it to know and understand itself. This view of what we are in the grand scheme of things is open-ended, full of endless puzzles, problems and possibilities, and I find it wonderful.

Every time we have made headway in understanding how the world works, we have done it by moving away from the supernatural and towards the natural—there is not a single exception in all of history. Gods and spirits become ever more irrelevant, and their retreat reveals a multi-layered web of mechanisms, from microscopic to cosmological, far more elegant and subtle than any ancient or modern superstition. We humans have a wonderful opportunity, now that we’re here, to discover and understand ever more and more of it.

There is no evidence that the Cosmos was made for us but, as we come to comprehend it better, it becomes clearer and clearer that we can use our knowledge to make it more to our liking. Rather than despair at its cold vastness, we should rejoice at the opportunity to understand and shape it to our advantage. We are not merely the subjects or playthings of some god. Whatever is physically possible, given enough knowledge, we can achieve. Even if the Universe doesn’t care about what happens to us, it is more than enough that we do.

It is undoubtedly true that the knowledge we create could lead us both to flourishing or destruction. There are real risks ahead, but the greatest risk is to content ourselves with ignorance and superstition—this will doom us to stagnation, squalor and, inevitably, extinction. So I say we go for it.

Moral Rules

A purely physical, mechanical Universe is amoral by definition. Fundamental particles have many properties, but moral values are not among them. Whatever our values are, they must be emergent phenomena which arise from the complicated interactions of lower-level mechanisms. Values are thus not absolute; they are not really ‘out there’ in the same sense as fundamental particles. This doesn’t mean they are not real, nor that they are arbitrary. It only means that they are constructed and, indeed, they can even be objective. I have found that it is helpful to distinguish between the absolute and the objective.

By absolute I mean that which is ‘really’ out there, whereas the objective is that which is true about what is absolute plus a few constructions. A useful example that illustrates this is the game of chess: given the rules and the objective of the game, there are objectively better and worse ways to play—but the game itself is made up (that is, constructed). We can imagine a world where chess never existed without incurring in any logical contradictions (a condition philosophers sometimes describe as contingency1); indeed, that was the way things were for most of the Universe’s history. Even so, one could not say that the rules of chess are arbitrary—they are designed to make the game interesting and playable.

Like games, values are constructed according to criteria. To build up morals, there are certain ‘givens’ within physicalism that serve as our starting points: pain and pleasure in their different forms, the finitude of life and the absence of an afterlife, and many others which we may call ‘human nature’. We wish to avoid poverty, disease, hunger, war, and plague; we prefer to keep our anxiety under control, and some guarantees about our minimum material security are appreciated. Family, friends, leisure, knowledge and art are valued almost universally. Most of us, including non-physicalists, agree on many of these givens and many more. But some moral systems are just wrong—objectively as well as absolutely—because they build upon mistaken or incoherent premises and principles, such as religion or ideology2.

It’s agreeing on the objectives where things start to get more difficult. Morally, these correspond to the ethical ends we wish to achieve, or what many would call our lives’ purpose or meaning. Again, I don’t think there is such a thing. There is what we would like to do with the time we have, and nothing more. I have not heard a single coherent or intelligible example of ‘the meaning of life’ that doesn’t collapse down to ‘the things we like to do with our life’. This is why agreeing on the objectives of our moral systems is so hard: people like and value different things. So far, the best solution we have come up with is liberalism: allow people to live their own lives as they prefer as much as possible, only stopping them when they interfere negatively with the lives of others. There are some difficulties and tricky cases for this framework, but all other alternatives tried so far have been much worse.

There is currently a lively debate about whether liberalism is enough to keep humanity going and motivated. I am content to spend my days thinking about physics, computers, classical music and literature, to try to make the best of the time I have with my family, and to hope I have a dignified, graceful exit from this world many decades from now. But many others want a big cause or purpose to be defined for them, or even imposed. As traditional religious belief fades away, other kinds of illiberal moral frameworks are taking its place. For now, I think liberalism is still the best option for everyone, but it will have to be defended forever because it is so unintuitive and unnatural.

Science and Happiness

In order to change the world, one must first know how it actually is and how it works. It may be possible to delude oneself into being happy despite being mistaken about reality, as with religious belief, but it will be impossible to make any progress. Magical thinking only stops further understanding of the mechanisms that actually rule our world. “God must have wanted this” might make people feel better in moments of hardship, but it has never gotten rid of any disease, communicated people instantly across the globe, nor made crops more resistant to plague or famine. For the hundreds of thousands of years that magical thinking was dominant, humanity made almost no progress.

I agree with Yuval Noah Harari when he says in Sapiens that the biggest scientific discovery of all time is the discovery of human ignorance. It used to be that truth and knowledge were considered to be whatever the ruling cleric, emperor, or great leader decreed them to be. It didn’t matter if that led to thousands starving to death, or to be slain in the battle field for nothing. To say that the gods or their representatives on Earth were mistaken was simply inconceivable. Today we know better.

Though it is still widespread among the general population in their private lives, magical thinking has been completely banished from science3. Whatever religious rituals individual scientists may join on weekends, if any, when they actually do science they are atheist materialists, because the world behaves exactly as it should if it were godless and material. How science actually generates knowledge is the subject of many books, but here it is enough to point out that it is a networked process that seeks to understand reality, actively assumes there will be mistakes, looks for them, and rewards those who find them.

Science can tell us how the world is or, at least, tell us how it is not, by ruling out ideas that don’t work. It provides perspective and invaluable information about what is feasible, and gives us the technical know-how for the things we want to achieve. But it cannot tell us what we should want to achieve.

I am broadly sympathetic to the view that science can, and should, determine our values. Moral realism, the view that moral values are absolute, is the foundation beneath this. However, I don’t think it works. Remembering the absolute vs. objective distinction from earlier, science aims to incrementally discover and understand the absolute, even if it never quite gets there. If moral values were absolute, then yes, it would follow that science could discover or establish them at least in principle. But I don’t think that can work, for reasons I explained in the previous sections. The short answer follows from physicalism and reductionism directly: moral values are not properties found in the fundamental physical world, and there is nothing but the fundamental physical world.

As I said earlier, I think morality can be objective, but not absolute. Once we agree on what we ought to do, then there are better and worse ways of going about it, just like once chess has been invented there are better and worse ways to play. Morality can thus be informed by science, no doubt. And science can help to knock down faulty moral systems, too, by showing that their premises are wrong. In other words, science can tell us what our ‘givens’ are: the minimal, non-optional rules of the game and its starting position. Once we have further agreed about our objectives, then it can tell us if and how we could achieve them. But it can't tell us what our objectives ought to be4. Notice that this concedes nothing to the relativists: Islam and Communism are still wrong, because they have the wrong ‘givens’. I’ve gone back and forth over this many times over the years, but I think the better arguments are on the objective-constructivist, as opposed to realist (let alone relativist) side.

The Good Life

How then, should we spend our time? First, constructivism is a fancy word for well-now-that-we-are-here-ism. Second, liberalism takes the individual as its starting point. Together, they imply that each one of us should build his or her own version of ‘the good life’. There is no third principle establishing what this looks like nor that it should be easy.

To be an individual seeking self-fulfillment doesn’t preclude one from drawing upon the experiences of others. There is no need to relive the whole of human experience for oneself. Culture, literature and mentorship are unsurpassable ways of catching up. I will now go on what will appear as a tangent, but I assure you that it connects with ‘the good life’.

Discipline presupposes an objective. It’s no good getting up very early for its own sake and nothing more; that’s just masochism. But, if one wants to achieve a certain level of fitness, say, and one also has a full time job and a family, there may be no other choice. A disciplined person will get up early to train and, crucially, will not depend on outside punishment or reward to do it. She will push herself regardless of what others think about her fitness, and independently of any help form trainers or workout partners.

This internal motivation is key for pursuing any goal and, properly channeled, can lead to great productivity. From the outside, it can sometimes look like an obsession. And indeed, most of the great artists, discoverers, and inventors of history have been quite obsessive. But it is also the source of stubbornness, ideology, superstition, and crackpottery. It is not merely enough to pursue interests with relentless discipline: one must also pursue worthwhile interests. How can one know what these are? Well, there is a straightforward, systematical method: try as many as you can. And that is a trap.

First, it’s a trap because there are way too many things one could pursue in life, and the exposure to many will necessarily be shallow and meandering at best. Second, many subjects are dead ends or simply wrong, though sometimes in not so obvious ways. Again, religions and political ideologies are good examples of this. It’s one thing to be well read about religions; it’s quite another to try to bring oneself to practice as many as possible. The former will give one perspective, and will ultimately help one realize how unsound and intellectually feeble the different creeds are; the latter will be a lifetime of mostly wasted time and quite certainly money, not to mention the enduring of inane prohibitions, sexual repression, and general stunting of the intellect.

But there are many not-so-obvious examples, and things can go wrong even when there’s the discipline to pursue a legitimately productive or rewarding interest. For every ‘self-taught’ musical virtuoso one sees in the media, for instance, there are dozens or hundreds of failed musicians who went down a rabbit-hole of obsolete methods, bad technique, and even physical injuries trying to learn an instrument on their own. Each one of them was convinced that they could do things their way, rebuild all of human musical know-how from scratch, and even surpass it. Many of them could have actually been great, if only they had had some humility and the right orientation to begin with.

And this is where culture, literature, and mentorship come in. One doesn’t have to rediscover the world from scratch to know what things are worth pursuing and how. Some sources of reward are already part of our nature, such as spending time with friends or family, or cultivating interests first found in childhood (a musical instrument, sport, chess, or maybe dinosaurs). For other things, luckily, one can make quite a lot of headway by reading books, watching films, or asking a grown-up. This can still take a long time, but eventually some interests settle enough to serve as anchors while others are explored more tentatively.

I do not have a ready-made recipe for what constitutes a good life in general, except for the very broad items of friends, family, and leisure that I mentioned in passing before. I don’t like to travel or even leave the house much, though I see that for most people it’s the opposite. I enjoy getting lost in physics, mathematics, a good book, an instrument, or a good film. The only constant difficulty I have is that these activities require being alone most of the time, which complicates the part about friends and family. It also seems increasingly clear that social media is a trap.

Philosopher Daniel Dennett has stated that happiness lies in finding and devoting yourself to a greater cause. I don’t know that I would call any of the things I enjoy a ‘cause’ in that sense, but I do know that what makes their pursuit even possible is liberalism, broadly construed. So I guess that’s my cause.

Salvation: Individual and Social

As will be clear at this point, I don’t think there’s any such thing as salvation in the religious sense. The Universe doesn’t know or care that we are here and, when we’re gone, won’t even notice. I find the hesitation to say this from people who understand it frustrating. There is no evidence for the afterlife or the supernatural, there never has been, and people who know this should say it when it is pertinent. We know what it’s like to not be alive, because that was the way things were for us before we were born, if ‘were’ is even the right term. Nothing is neither good nor bad, because it’s just nothing.

While we are here, though, is another matter. Salvation as a species will consist of maintaining our current state of continual progress. Thus, there is no final endpoint when we can declare salvation has been achieved. As I said at the beginning, we have a once-in-a-solar-system opportunity (maybe once-in-a-galaxy?) to hold off entropy for a while and even enjoy it. There is no value lost in the fact that our lives are finite. If anything, it makes them even more precious. We are at the current foremost point of an unbroken chain of causality going back at least 14 billion years, including the transition from one human generation to the next, and I think that’s pretty cool, even if the Cosmos doesn’t care. I think it’s pretty cool that I get to think it’s pretty cool. Animals like my dog don’t get it, and no humans got it either for ages. Now we do. This is a major qualitative jump compared to all other processes in the Universe that we know of.

Keeping our open-ended situation will be difficult. Liberalism just doesn’t sound like a plan: “just let everyone mostly do their thing and make sure to keep it going”. Most of the world doesn’t do things that way even now. And yet, it works. Or at least it has until now.

The main drawback of giving everyone as much liberty as possible is that some use it for nefarious purposes. The damage they cause has been contained up to now, since even a well-organized group of barbarians cannot destroy civilization by themselves with barbarian-level tactics and armament. But we may be on the verge of massive destruction being made more available to more people, along with the knowledge of how to use it. Even if small bands of savages can be contained, there are still entire illiberal countries that may wreak havoc, as well as authoritarian contingents within free countries. Science and history have taught us many lessons, but it is not clear that enough of us have learned them.

There is still much existing knowledge that hasn’t permeated fully to all people. As I write this, both vaccine denial and flat-earthism are not just alive, but on the upswing. Recent polling finds that people are increasingly dissatisfied with liberal democracy, even as we know more and more about the atrocities committed by its alternatives now and in the past. In the short term, this is very worrying to me.

In the long term, however, I think physicalist liberalism can and will recover, since reality cannot be decreed out of existence, either by the mob or by some dictator. Even if there are coming setbacks, authoritarianism will have to give in eventually, since it is incapable of progress. Even now, illiberalism survives only by parasitizing the knowledge and productivity of modern free societies. The only way this long-term victory of liberalism could be avoided is if there’s a cataclysmic event to wipe everything back to zero for good, such as nuclear annihilation.

For me, salvation consists in keeping my own state of continual progress. If anything terrifies me, it is to imagine merely droning on doing and knowing the same until I die. It always disappoints me to see people content with not knowing, or at least not knowing more. I constantly begin personal projects, such as learning musical instruments, science, and languages. If something doesn’t work out, I cut my losses and try something else, or come back to it later when I’m better prepared. I know it doesn’t sound grand or glorious but, from my point, I kind of already am in a state of salvation, and I’d like to keep it going.

A subtle point here is worth mentioning: a possible implication of physicalism is hard determinism, where all events are predetermined from the first moment of time. Under this scenario, chess, along with everything else in the Universe, really would be logically inevitable and thus not contingent.

Building upon faulty premises is also what allows religious believers and ideologues to invoke the ‘not a real X’ defense for their beliefs, because ‘X’ is always poorly defined. “Real communism has never been tried” fails for the same reason as “a real perpetual motion machine has never been built”.

In order to fully mature into sciences, fields like politics or economics first have to let go of their remaining superstitions. At this time, the biggest one remaining in both seems to be Marxism.

To push the chess analogy further, one could imagine using the standard board, pieces, and even rules but with a different objective, such as capturing all the opponent’s pieces rather than checkmating him.